The waving of the checkered flag at the Brazilian Grand Prix on September 17, 1988, marked the end of an era. A decade of exciting experimentation came to a close that day when the last ELF racing motorcycle completed its final race. In the 10 years leading up to that day, the ELF name had transcended its petroleum-industry roots. It had become synonymous with a series of ambitious, high-profile and determined attempts to expand the frontiers of motorcycle chassis design. ELF created an alternative motorcycle that would demonstrate its superiority on the most demanding proving ground-international roadracing competition.

ELF wasn't the first to experiment with alternative motorcycle chassis designs, but it was the best publicized and, thanks to the French petroleum company's vast resources, the best funded, too. Even if its two-wheeled experiments didn't radically alter motorcycling's future, ELF made chassis experimentation respectable. Inspired by ELF, countless designers the world over were encouraged to create the motorcycle of the future. ELF may not have been the first to dream up some of the ideas it subsequently claimed credit for (and patented to recoup some development costs by selling them to Honda), but it legitimized the effort. The actual design solutions ELF evolved over the years were overshadowed by its influence over motorcycle design. Thanks to its involvement in world championship roadracing, the alternative motorcycle design is more of a reality and less of a dream.

ELF has a long history of supporting new motorsports technology, and leveraging that support to build its brand. ELF sponsored Renault in the 1970s, when the French automotive giant introduced turbocharging technology to endurance racing and then to F1. Andre de Cortanze, one of the leading Renault designers during that period, came up with the A442 Alpine-Renault V6 turbo that won the Le Mans 24 Hours, and also developed Renault's first turbo GP racecar. An enthusiastic enduro rider on two wheels, he was also full of avant-garde ideas on motorcycle design, many of which incorporated lessons learned from the racing car world. Sharing these in conversation with ELF's marketing boss Francois Guiter during breaks in testing Renault, de Cortanze was eventually entrusted with a small budget for a motorcycle prototype to test his ideas. Thus the ELF motorcycle project was born.

The subsequent Yamaha TZ750-powered ELF X (for experimental) appeared in unfinished form at the 1978 Paris Show. The machine incorporated many of de Cortanze's principal design aims, which he summarized thusly: "I wanted to get rid of every preconceived notion I had of what a motorcycle should consist of and look like," he explained. "I wanted to achieve four aims: lower the center of gravity, incorporate 'natural' antidive suspension, reduce weight and eliminate the chassis completely as a separate entity. There were secondary objectives: to achieve an ideal 50/50 weight distribution, lower the frontal aspect to reduce the drag coefficient (Cx) and be able to change wheels quickly. I also hoped to improve airflow to the radiator for more effective cooling, and make the suspension and steering geometry adjustable quickly and easily in a way that we had begun to accept as normal on racing cars but which was largely unavailable then on bikes." De Cortanze was nothing if not ambitious.

The ELF X, built in de Cortanze's spare time at Renault with its passive blessing, established many of the design features that would become his signatures in future years. Parallel arms replaced a conventional front fork, and a single-sided swingarm held the rear wheel. The chassis was essentially deleted. The arms were mounted to plates bolted to the stressed-member engine. The fuel tank was located beneath the engine, and wind-tunnel-designed bodywork maximized aerodynamic efficiency. The ELF X was a fundamentally radical racing machine.

Michel Rougerie undertook initial track testing in 1978, prior to its racing debut at Nogaro later that year. But development was slow, hampered by problems with a Yamaha two-stroke that proved unsuitable for use as a fully stressed member, and de Cortanze's part-time involvement. But ELF X made a sufficient impression for none other than Honda to express interest. A private 1979 test session with a Honda test rider confirmed that interest. Soon a collaboration was launched between the Japanese manufacturer and the French fuel giant. Honda agreed to supply ELF with works 1000cc RSC endurance engines for the 1980 season, around which de Cortanze would build an all-new bike incorporating the lessons learned on the ELF X.

The result was the ELFe (for endurance) that debuted at the 1981 Bol d'Or and, with substantial ELF backing, competed in every round of the World Endurance Championship until the end of 1983. Though the ELFe was very fast, often qualifying on pole and leading early laps, the chassis was unreliable. Refined to the purest form of de Cortanze's ideas, it finished third in the final 1000cc TTl/Endurance race at Mugello in 1983, then captured six world-speed records at Italy's Nardo test track in 1986 in ELF R (for record) form, fitted with special streamlining.

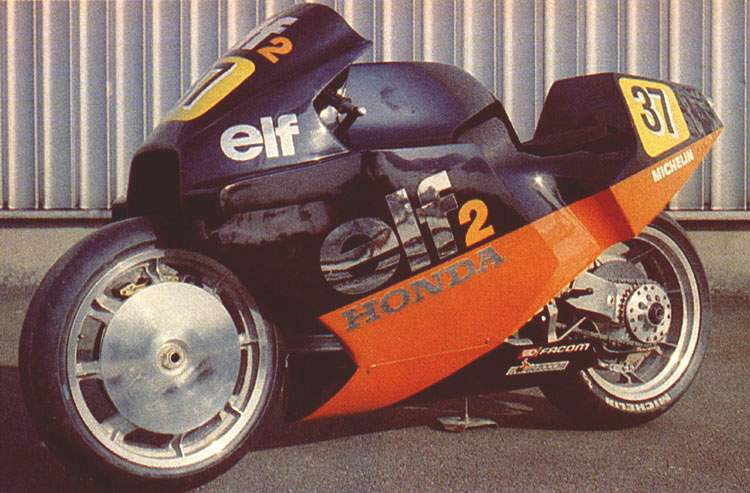

The end of one-liter endurance racing at the end of the 1983 season enabled ELF to enter the higher-profile world of prototype GP racing and reap better promotional dividends. Honda supported them with three-cylinder RS500 engines, and in June of 1984 the ELF2 began testing in the hands of de Cortanze's longtime collaborator, Christian Leliard. Its most interesting feature was a revolutionary steering system, consisting of handlebars mounted to a crossmember and rigged to move fore and aft, rather than pivoting side to side. The suspension was also adventurous, utilizing a pair of specially made Marzocchi shocks beneath the engine that worked in traction rather than in compression.

The Black Bird, as it was dubbed by the French press, never raced. Riders found the curious steering system hard to get used to (push-starting on a crowded GP grid would have been exciting!). The proximity of the suspension pivots and insufficient damping from the special Marzocchis led to incurable handling problems. It didn't debut until a year later at the French GP at Le Mans, by which time it morphed into the less-quirky ELF2A, with proven ELFe-type hub-center steering and revised suspension.

At this point de Cortanze was forced to give up his involvement with the ELF project, which had been dwindling due to the pressure of his new job with Peugeot. Guiter entrusted the next stage of development to race manager Serge Rosset, who had been running a pair of NS500 Honda triples in ELF colors while waiting for the ELF2, and engineer/draftsman Dan Trema. Guiter and ELF management were hungry for results. With this in mind, Rosset and Trema collaborated on the relatively conventional ELF3, powered by works Honda NS500 engines. British rider Ron Haslam, fifth in the World Championship the previous year, would ride it.

Rosset's commitment to produce results had immediate effect. Haslam used the ELF3 to score ELF's first 500cc World Championship point in its first race at Jarama in 1986. Haslam was a superb test rider, forging an unlikely but lasting close relationship with Rosset. In the hands of this Anglo-French alliance the ELF3 progressed quickly, winding up ninth at the end of the season ahead of the works Suzuki team. The breakthrough had been made: Here was an alternative design that worked as well as a conventional one right out of the box, with an entire development cycle ahead.

Honda agreed, signing a secret 1985 agreement to evaluate ELF's patented designs with an eye toward production applications. Commercial negotiations to lease the patents began, and an agreement was signed in September 1987. The first Honda to incorporate ELF's patented single-sided rear swingarm (henceforth dubbed 'Pro-Arm') had already been introduced to the market. Trema holds the distinction of being the first outsider to spend a fortnight working inside HRC. He visited there late in 1986 to design parts for the new ELF4 and to work on the NSR500C V4 engine. Delays meant Haslam started the season riding a standard NSR Honda in ELF colors, but he finished fourth in the 1987 points table though he only rode the ELF4 in the final few GPs. Serious brake problems delayed the bike's race debut. A proposed carbon-fiber chassis was rejected after laboratory tests showed its failure to meet minimum safety standards.

Instead, Rosset and Trema redesigned the V4 ELF for 1988. That was the final year of the ELF bike project, at least partially because of concept champion Guiter's imminent retirement. Employing a cast-magnesium chassis and Honda-supplied Nissin front brakes, the ELF5 worked well enough, but the conventional opposition had become stronger and more sophisticated. Three seventh places and 11th in the points standings were the fruits of its disappointing final season; an anticlimactic end for a project that had promised so much and actually delivered such useful technology.

In the end, the ELF roadracing effort went out with a whimper instead of a glorious bang. But there was one race victory in the 1986 Macau GP, on a circuit where Ron Haslam is the acknowledged master, to point to as proof that the unconventional motorcycle really did work. Honda obviously thought so too. Every Pro-Arm-equipped VFR Interceptor that rolls out the door reminds us of this fortuitous collaboration. Who are we to argue that?

The final edition

Riding elf5,The End of This Innovative Line

The ELF5 that carried Ron Haslam to 11th place in the 1988 500cc World Championship (sevenths at Spa and Brno were his best results that season) was the ultimate expression of the project's design philosophy. I had ridden most of the previous ELF designs and was keen to sample the last in line. I got my chance after the 1988 racing season at circuit Paul Ricard during the Au Revoir les ELF test day. The ELF5 evolved from the ELF3, with a true frameset and a single horizontal front swingarm using a MacPherson-like strut and single Showa suspension unit. Team Manager Serge Rosset called this sophisticated, highly adjustable front-end design the VGC System, for Variation Geometrique Controle, or controlled geometric variation. To reduce weight, most chassis and suspension components were made from cast magnesium. The 1988 ELF5 actually used the 1987 Honda NSR500 two-stroke engine, as the '88 version wasn't available early enough to allow development of the cast chassis.

The riding position was more extreme than a conventional NSR. You sat farther forward to get more weight on the front wheel. On track, the ELF5 pushed badly, sending me off the outside of the fast sweeper at the end of the Mistrale Straight and again at the tight left after the Pif-Paf chicane.

Haslam explained you couldn't ride the ELF5 like a traditional GP racer, braking late and steering with the rear on the way out. The ELF5 needed lean angle to turn. When steered like a conventional GP bike, it felt heavy and unresponsive. But apex the corner in a classical Mike Hailwood style and steering became neutral, though still heavy. It was stable but far from nimble, unlike the lighter-feeling ELF3, which felt much more controllable.

What you got in exchange for heavy steering was unparalleled braking stability. Because of the hub-center design's constant steering geometry, you could brake harder and later than on any conventional machine, and turn under braking without upsetting the handling. Another advantage of the ELF5 was exceptional chassis adjustability; all the usual suspension settings, plus head angle, wheelbase, trail, ride height front and rear, as well as weight distribution were all readily changeable.

It didn't win a championship, but with the ELF5 Serge Rosset's dream of une moto a la carte-a bike that could be easily altered to suit the taste of anyone-had been realized. As a believer in the ELF philosophy from the start, I still can't help but feel a sense of unfinished business surrounding the concept. As former ELF rider Dave Aldana wrote in a sidebar to my test of the ELFe back in 1983: "Nice bike, but not done yet."

I'll go along with that.